1, Tsuzure (Tapestry)

2, Tatenishiki

3, Nukinishiki

4, Donsu (Damask)

5, Shuchin

6, Shouha

7, Futsu

8, Mojiri-ori

9, Honshibo-ori

10, Velvet

11, Kasuri-ori

12, Tsumugi

1, Tsuzure (Tapestry)

Construction & Composition

With an application of plain-weave technique, the pattern of a tapestry is woven by the weft, which is three to five times thicker than the warp, where the weft wraps around the warp. Therefore, the warp does not appear on the surface of the finished fabric.

In addition, each part of the pattern is woven without having the weft pass through the entire warp, regardless of the action of the Jacquard loom. Therefore, there are small spaces between each thread, because the weft does not pass through the entire fabric. As a result there are plain, unfigured areas in the pattern of the fabric. This particular way of tapestry weaving involves small techniques. For instance, the weaver’s fingernail tips are filed into zigzag shape in order to pick up and cross threads while working on fine detailed parts of the pattern. Complicated patterns often require an entire day to weave just 1 square centimeter.

History

The world’s oldest tapestry dates back to 1580 B.C., the time of 17th Egyptian Dynasty period. In Japan, some time during the middle of Edo period, documents state that Sehei Izutsuya was the first person to weave tapestries in Nishijin.

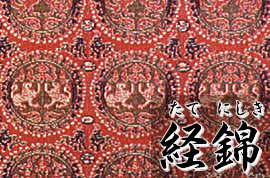

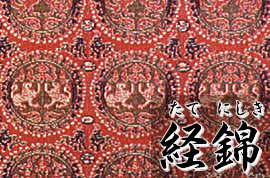

2, Tatenishiki

Construction & Composition

Tatenishiki is literally a Japanese brocade, and the texture of the pattern is woven by the warp. If a textile includes three colors, the textile is woven with three warps as a set to create a base and a pattern with an intricate action of alternating ups and downs to produce double-sided weaving.

The more colors the textile uses, the more warps it will require. Therefore, natural color combinations are limited, since the technique becomes much more complicated, hence, weaving large patterns with this kind of method will become very difficult.

Most of Tatenishiki weaving is done on a double warp, whereas quadruple or sextuple warp is rarely found. In addition, the base is woven in stripes with several colors in order to show a variety of color schemes.

History

Tatenishiki has the longest history out of all the Japanese brocade weaves, which is characterized by the patterns and its use of various colors. The origin is unknown, however, Tatenishiki is said to have originated from more than 1,200 years ago. Although there are no sources that state the time period when the weaving technique was introduced to Japan from China, but ancient articles left from the deceased from Asuka and Nara periods (7th-8th century), are still displayed at Horyu-ji temple and Shosoin today.

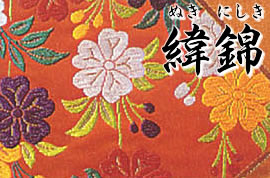

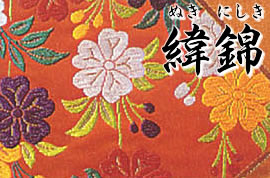

3, Nukinishiki

Construction & Composition

Nishiki (Japanese brocade) is a general term of textile that is woven with several threads to create patterns and is often used as a pronoun of gorgeous textiles. Many of Nishiki textiles that use Enuki (wefts used for the surface of the pattern), have proper names distinguished by a variety of weaving methods and patterns. “Ito-nishiki” represents most of Japanese brocade by using three-twill weave on the base, and Enuki wefts for both sides.

History

The history of Nishiki is very old. Various Nishiki textiles are woven with the weaving methods and patterns of Tatenishiki and Nukinishiki, since the time of the great prosperous time of Nara period in Japan and Han dynasty in China. During the Heian period, variations of Nishiki textiles were further subdivided with specific names, such as Karanishiki, Yamatonishiki, Itonishiki, etc. In addition, diversity and complexity further developed in Nishiki weaving during this time as we can see from Nukinishiki, by looking at the way the use of threads changed from Nara to Heian period. Sources indicate that “Itonishiki” represents Nishiki textile and that it was first woven in Nishijin during the Tensho era, which closely followed the weaving methods that were widely used in China during the Ming dynasty. Nishiki, is woven in a way so that threads are raised to the surface on the back side of the Enuki for the pupose of creating unique patterns and this method of weaving became frequent in use and was eventually for obi (kimono sash) material in Edo period.

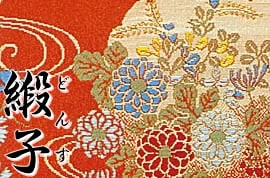

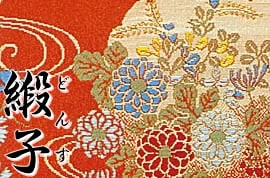

4, Donsu (Damask)

Construction & Composition

Shusu-ori (satin weave) is one of the weaving methods of the Sangensoshiki weaving foundation. Shusu-ori is a textile, in which the threads of either the weft or the warp rise to the surface of the textile by reducing the crossing point of the weft and warp, and scattering the points to avoid continuity. The Donsu or damask weaving requires “five-piece Shusu”, which uses sets of five wefts and warps for either the base or the family crest pattern.

History

Fiber-dyed damask was first transported from China, by sea along with gold brocades and other goods in the Kamakura period and many more were imported during the Nanboku-cho and Muromachi periods. Some of the imports are called “Meibutsu-reki” and were introduced in this time period with great care. damasks were woven at Nishijin, after multiple researches were done on these imported damasks.

Moreover, damasks were mainly woven for men’s clothing in the beginning, while the use of Damasks for women’s clothing and obi were used later on starting in Genroku era. Women’s obi became popular and spread widely mainly after the Anei and Tenmei eras and in the golden age period of the 10th-20th centuries of Meiji period.

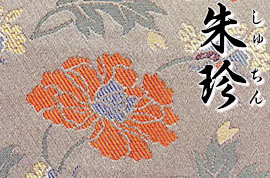

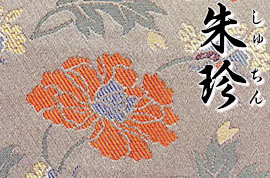

5, Shuchin

Construction & Composition

While Shusu (satin weave) normally requires a 5-piece or 8-piece Shusu-weave system, the character for Shusu “繻子” was origianlly written as “八糸緞” (also read as Shusu), meaning 8-thread damask. Similarly, for Shuchin “朱珍” weave (satin weave with raised figures) was originally written as “七糸緞 – Shichishitan” or “七彩 – Nanasa or Nanase”, meaning 7-thread damask, according to ancient records. In addition, patterns woven with several Enuki on the base of Shusu textile, signified the change of character used in the name to “七”, meaning seven. The difference from Donsu or damask weaving is that Shusu “繻子” weaving does not have the Jiagemon (a method of weaving to reveal the base threads), while the Donsu does.

History

It has not been long in terms of history, since Shuchin weaving began in Japan. The first weaving of Shuchin began in Muromachi period, by following the textile methods that were transported from China. However, such unique marvel and beauty of the textiles fascinated the people, so they continued to introduce textiles from China up until the Edo period. The technique of changing the shuttles of Enuki numerous times, allows for gorgeous, colorful patterns to be displayed on the base of Shusu, giving the fabric smoothness and gloss to its finish. Also the use of the fabric was further expanded, by producing luxury items by incorporating gold and silver foils.

During the second half of the Edo period, Shuchin fabrics became the must-use textile for Noh stage costumes and for women’s obi.

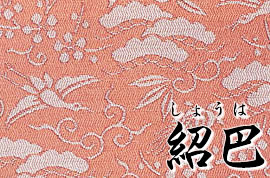

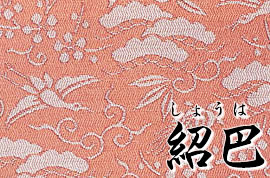

6, Shouha

Construction & Composition

Using strong twisted thread with the warp, the base pattern shows small crosswise herringbone patterns or mountain-type patterns. The base of the composition is not so thick, so it was traditionally woven for the back parts of Haori (Japanese formal coats) or coats.

History

It is unfortunate that there is no evidence of the Shouha weaving method recorded in terms of its historical facts. However, Shouhagire (fabrics woven by the Shouha method), found in the Meibutsugire (things like pouches for tea ceremony tools) Gold Brocade, a category of textile goods, was woven at Nishijin and was deeply cherished by Shouha Satomura (1524〜1602), a renga poet, who was a disciple of Sen No Rikyu (the great tea master).

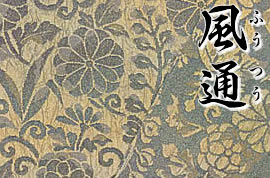

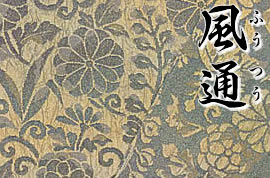

7, Futsu

Construction & Composition

The cross-section of textiles is normally single layered, however, some textiles with double or triple layered cross-sections are called multi-layered textiles, which include the Futsu weaving, characterized mostly by its multi-layers. The pattern of the textile appears on the surface by weaving different colors of threads, alternating in up and down for double-layer, or up, middle, and down for triple-layer weaving. Double-layer weaving is called, “Nishoku (double-colored) -Futsu”, which is capable of displaying both colors at the same time on the front and back sides. Nishoku-Futsu is commonly is used for Nishijin’s Kijyaku (a standard length of material used in a kimono), bag, obi, and other items alike.

History

According to the book, “Tankai”, “Futsu is well regarded also by the country for its fame and prestige… ” The name of this unique weaving was compared to other foreign textile weaving method names, such as the Mogol or Mughal weaving. The current name had supposedly become known after the Onin War, and was once more recognized when the techniques were introduced from China’s Ming dynasty. The weaving method of Futsu, is best described for its techniques that create small spaces in between the double-layer of the textile. The textile system had already existed as the legacy of Horyuji temple, so it carries a long history.

8, Mojiri-ori

Construction & Composition

Normally, the warps of textiles are parallel to each other, and wefts cross over perpendicular to the warp to produce the weave of the fabric. However, the Mojiri warp is formed on the right and left sides of the foundation of the warp. Aside from the more common Ji heddle, in this particular weaving style, a special heddle is necessary, called the Mojiri heddle (Furuhe). It is often called Karami-ori weaving, which includes materials such as “Sha” (silk), “Ra” (lightweight fabric) , and “Ro” (gauze).

History

For the Mojiri-ori, the side warps are intertwined together to show characteristic of knitting. The most complicated pattern appears on the “Ra”, perceived as the oldest out of Mojiri-ori method. The fact that the elaborate “Ra” was carried out already during China’s Han dynasty (around the beginning years of A.D.) is well known from the artifacts discovered from the Mawangdui Han tombs.

In Japan, it was used in Tenjukokushuucho, an embroidery illustrating a mandala, from Asuka period, and a variety of articles from the Nara period are introduced to Shosoin. However, Mojiri-ori had gradually declined after the Heian period, and finally disappeared after the Onin War. A revival of the Mojiri-ori was triggered by Tajiro Sasaki’s effort during the Showa era and later on, the most simple “Ra” fabric was being woven during the Edo period.

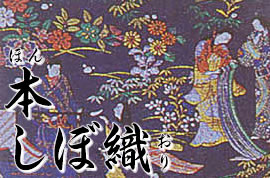

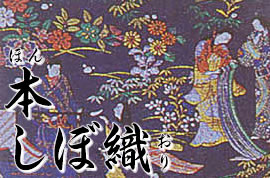

9, Honshibo-ori

Construction & Composition

Honshibo-ori uses dyed degummed silk threads for the warp and weft; the warp is loosely twisted, and the weft is tightly twisted. The first round of the twisted weft is woven and is then subjected to a glue paste and before this glue dries, another round of even more tightly twisted weft is woven through. After alternately weaving two strands of the right twist, and left twist threads at a time, the fabric is then soaked in lukewarm water, and is massaged vigourously to bring out the grain, the bumpy texture of the fabric to the surface.

History

Chirimen (silk crepe) and Omeshi (stripe crepe) are examples of silk woven textiles with an embossing process, in which the texture of the silk crepe is critical for piece dyeing, including Yuzen dyeing. While these kinds of weaving methods were already recognized in ancient Japan, Chinese-made textiles were introduced through their interactions at overseas during the early period of the modern age and eventually became the foundation for today’s weaving. Some discovered examples with this kind of weaving include the crimson colored clothing of Shingen Uesugi that was found as a memento, and Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s battle surcoat woven with white silk crepe. Considering these mementos, it is believed that Japan began weaving such fabrics after it was introduced to the country. However, a more full-scale production of weaving didn’t start until the beginning of Edo period, where weaving production started in Nishijin.

Although many silk crepes, and silk garments of Shu (embroidery) and Some (dyeing) are introduced, all of these are different from their modern versions, particulalrly in its lightness and thinness. In addition, the name of Omeshi (stripe crepe) was derived from Ienari Tokugawa, the 11th Tokugawa Shogunate military director (in office: 1878〜1837), who preferred to wear silk crepe with small greyish-blue checkered design. These dyed silk-thread crepes are called “Omeshi” (the honorific term for “wearing” used towards a senior), since it was worn as a clothing of a Shogun (general). After the Omeshi was introduced, its unique and stylish look was cherished by the people of Bunka-Bunsei era and as a result, this weaving method was not only applied in making men’s clothing, but also in women’s clothing. During the trend, an equal proportion of men’s and women’s clothing were woven during the early years of Showa era. Until the beggining of WW2, it was represented as a high-class item of clothing.

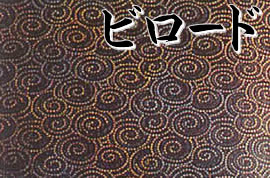

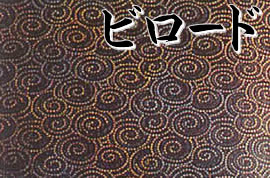

10, Velvet

Construction & Composition

Nishijin’s velvet is a wired velvet, in which wires are woven in from the sides to create unique feathers and loops. Afterwards, the warp around the wires is cut to raise the nap (raised fuzzy surface), and loops are formed by pulling out the threads. In the weaving method, called “Honten”, the weft is first woven three times normally, then the pile of warp is raised from the base of the composition, and then a wire is inserted through. 50 strands of wire, each 1mm in diameter and 50cm in length, are woven through, roughly every 3cm.

History

The velvet is known for its attractive, smooth touch and soft gloss and it was first introduced to Japan through the Nanban trade during the 16th century. The description given by missionaries who came to Japan, state that people, including Nobunaga, a powerful daimyo of Japan, were fascinated by the mysterious textile. A cape with peony arabesque design that was once owned by Kenshin Uesugi, a daimyo from the Sengoku period, is the oldest known relic made with velvet. The weaving method was finally clarified in Japan around the early Edo period, and production started during Tenpo and Keian eras. In the notes of “Nishijin Tengu Hikki”, the weaving method was introduced to Seiuemon Yorozuya at Imadegawa-Horikawa-Nishiiru during the Genroku era.

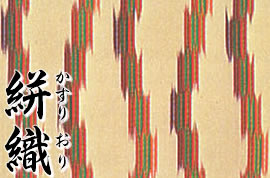

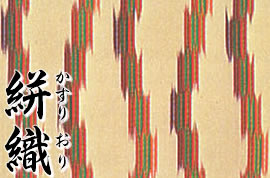

11, Kasuri-ori

Construction & Composition

The pattern of Kasuri (splash or dye pattern) is created by fibers dyed specifically to create patterns, where the warp and weft are resist-dyed in some designs. This kind of weaving composition exists in Shusu (satin) weaving as well.

History

Kasuri is most well known for its simple weaving and had originated in India. It was gradually introduced to Southeast Asia including, Thailand, Burma, Java, Sumatra, Okinawa, and then finally to Japan. On the other hand, it was also introduced through Northern India from Persia, and eventually made its way to Europe. The oldest relic of this weave in Japan, is the gift that was presented at Horyu-ji temple from China, between the 6th and 7th century, in which there were several, different in color schemes and patterns. The

Taishikanto (a category of textile weaving design), well known for its design in red with cloud rising over the mountain, is woven by Tategashuri made with silk. While its actual background is unknown, various Kasuri weaving was devised upon simple weaving methods from various regioan throughout Japan, including Yuki (Ibaraki Prefecture) and Oshima (Hokkaido). The Kasuri weaving method was applied, especially in the pattern of Yagasuri of Omeshi, Noh costumes with Dankawari (a checkered-like pattern) design, and the back parts of Noshime costumes in Nishijin.

12, Tsumugi

Construction & Composition

It is a plain weave that uses degummed dyed silk fibers. Hand-woven silk floss is used for weft and warp, and Kasuri (splash or dye pattern), Shima (stripes), and Shiro (whites) are incorporated in the weave by using a handloom.

History

Tsumugi had developed over time as a kind of silk weaving. Using the hand-weaving method to weave silk wadding, allows for easy weaving of the strong fiber. In areas with sericulture, Tsumugi was actively produced as a private weaving industry, since the cocoon remains were usable. According to the Engi-Shiki (Japanese book of laws and customs), Tsumugi was found in various countries, and it was widely used due to its durability. Hitachi-Tsumugi (currently Yuki City) in the Kanto region of Japan was well known throughout Japan, and the Shinshu-Tsumugi was said to be the second famous area during the Edo period. Tsumugi of Nishijin is also called, “Miyako-Buri”, which incorporates embroidery into the design, maintaining the simple taste of Tsumugi weaving, to remind us of the sense and character of the city.